In January 1991, while most Americans were watching Desert Storm unfold on CNN, I was on a plane to Saudi Arabia.

I was 33 years old. A year earlier, I'd been a headhunter in Los Angeles. Then I met an Iraqi businessman living in Malibu who was looking for someone to scout business opportunities in the Middle East. He offered me a 100% commission deal — no salary, no safety net. Just a handshake and a chance.

I took it.

The Cold Call That Changed Everything

I arrived in Dhahran at about the same time the U.S. military landed. The region was chaos — 125,000 troops pouring into the desert, and the infrastructure couldn't keep up. I didn't have a plan. I had instincts.

So I did what I'd always done: I went looking for a problem to solve.

I found U.S. Army procurement officers working out of a tent. Not an office. Not a building. A tent in the Saudi desert.

I walked in and made a cold sales call.

They had a problem: 125,000 soldiers needed ice, and the two local factories could only produce 100,000 pounds a day — about 20% of what was required. Troops were overheating. It was a logistics nightmare.

I told them I could solve it.

I found additional ice production 200 miles away in Riyadh, arranged refrigerated trucks to haul it across the desert, and closed a $3.8 million contract to keep American soldiers supplied with ice for six months.

"The Gold Rush to Rebuild Kuwait" — Fortune, April 8, 1991. The article described how I "made a cold sales call to a tent of U.S. Army procurers" and built a multi-million dollar operation in a war zone.

Building a $30 Million Operation

With the ice contract as my foundation, I started looking for other problems to solve. The military needed generators — I found them. They needed laptop computers — I leased them. They needed supplies that weren't making it through normal channels — I figured out how to deliver.

Over the next several months, I parlayed that first ice contract into roughly $30 million in military contracts. Every deal started the same way: find the problem, build the relationship, close.

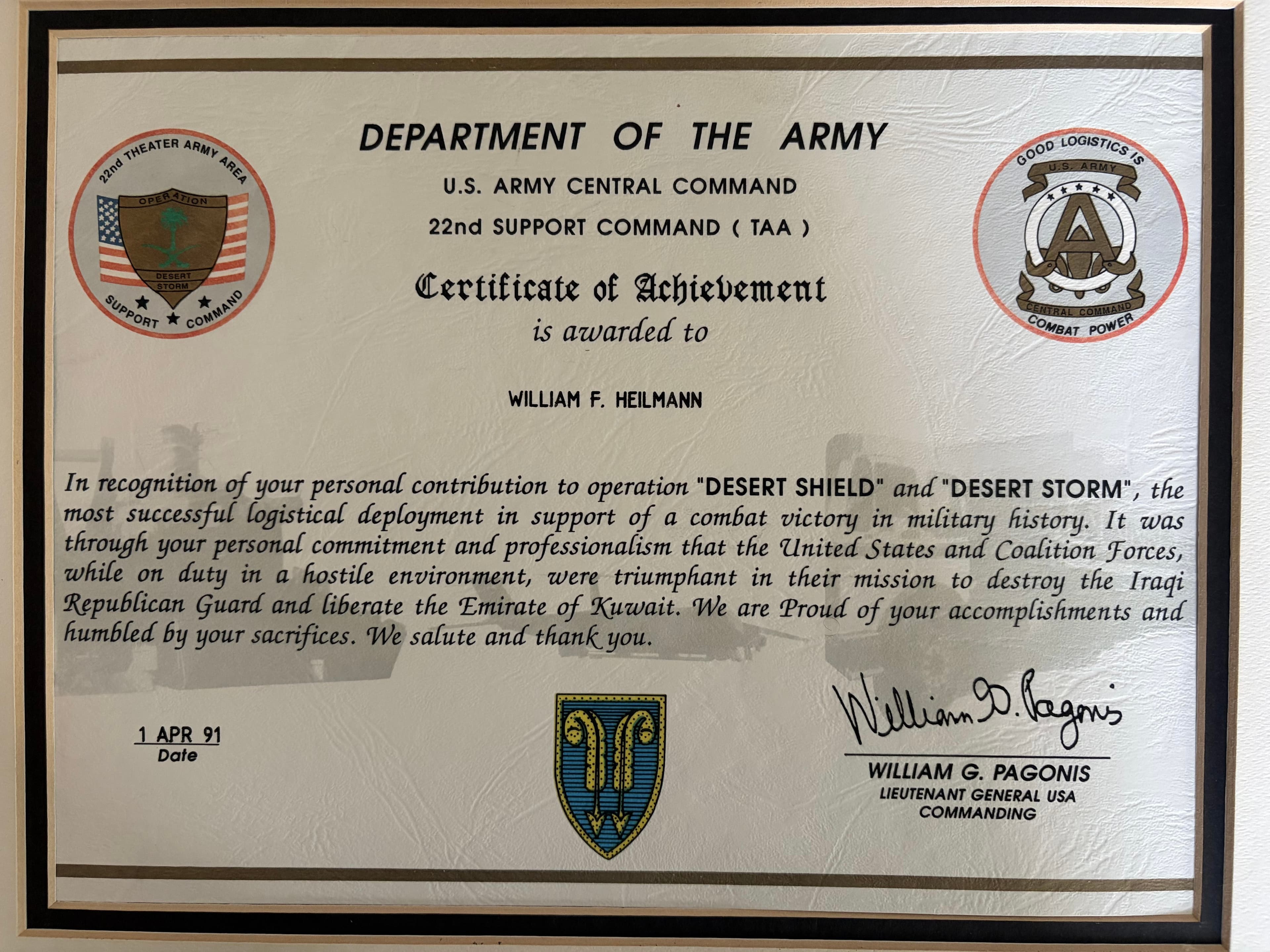

Recognition from the U.S. Army

On April 1, 1991, I received a Certificate of Achievement from the Department of the Army, signed by Lieutenant General William G. Pagonis — the commander who ran the logistics for the entire Desert Storm operation.

Life in a War Zone

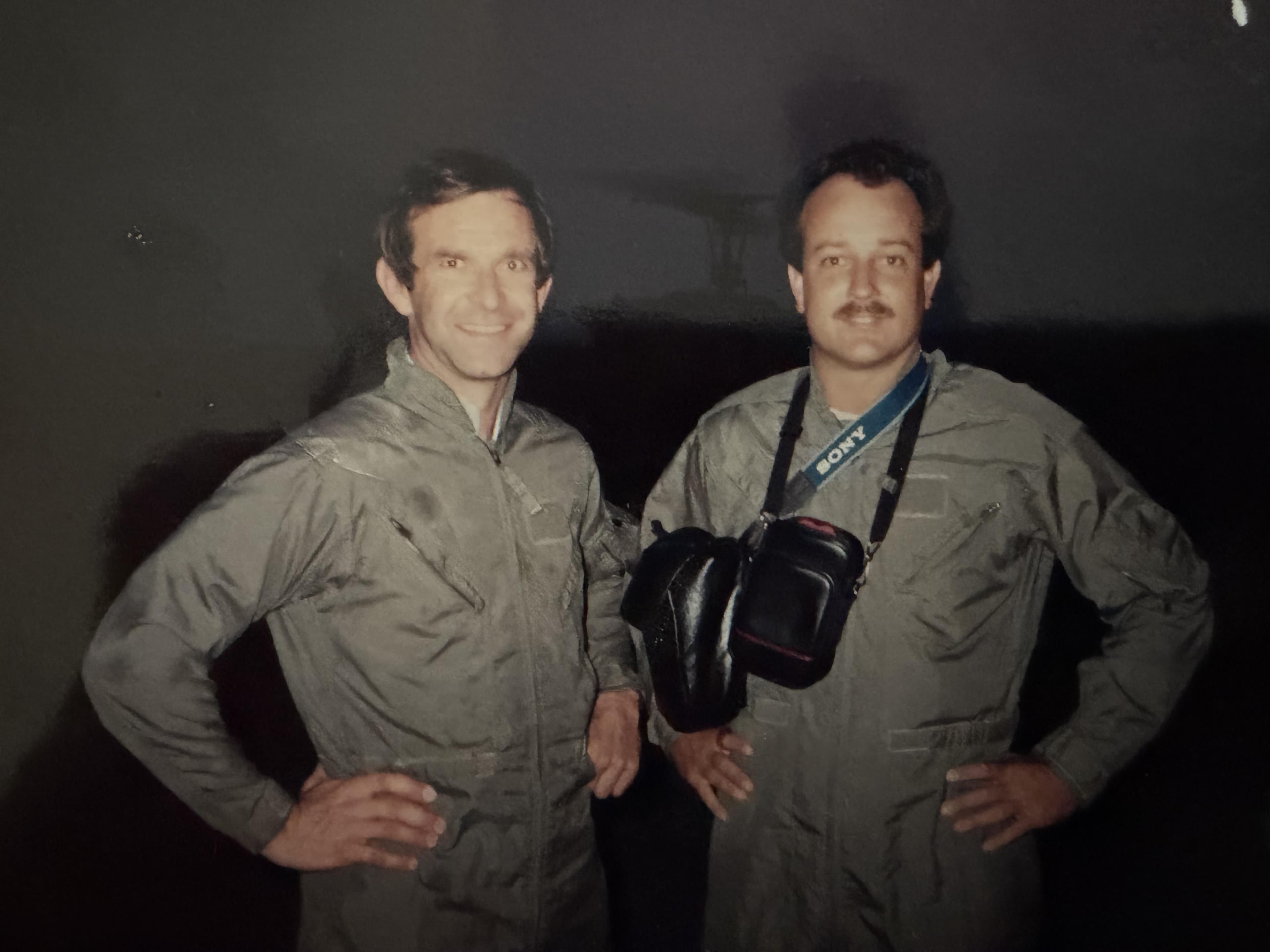

When you're operating in an active military theater, you see things most people only read about. I flew evening helicopter missions over the desert. I worked alongside soldiers, pilots, and officers who were putting their lives on the line.

After an evening helicopter flight over the Saudi desert, 1991. That's me on the right with the camera bag.

What Desert Storm Taught Me

Desert Storm wasn't just a chapter in my career — it was a masterclass in everything I still do today: find the problem no one else is solving; build relationships fast; execute when others hesitate; parlay every win into the next opportunity.

These are the same principles I bring to every executive I work with today. Your job search is your Desert Storm — unfamiliar territory, high stakes, and chaos everywhere. You need someone who's operated in those conditions before.

Ready to work with someone who's been there?

If you're an executive navigating a career transition, I can help.